Chord Substitution

When I started my series on chords back in January, I’d promised a lesson on chord substitution… here it as at long last! We’ll start with some basics:

What is a chord substitution?

It’s using one chord in place of another (or part of another) in a chord progression.

Why would you want to substitute a chord?

Well, you might have a progression that sounds good, but you want to see if it can sound better. Substituting chords can dress things up a bit. Or if you’re playing in a highly improvisational format, changing a chord to something close is one way to throw ideas at the soloist.

How does chord substitution work?

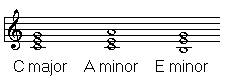

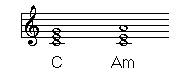

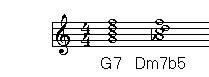

In two major ways: first, the chord might be close to the original – so it sounds ‘mostly’ right. If the chord called for is C major (made of C-E-G notes), you might try A minor (A-C-E) or E minor (E-G-B), which each have two of the same notes… it’s the one note that’s different which makes it a substitution. This is easiest to see in standard notation:

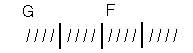

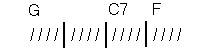

In the second way, the chord is different from the original, but leads naturally into it. These substitutions are usually for just part of the duration. In the following example, F major is played for two bars in the original progression. You might try C7 for the first bar, and F major for the second bar. The C7 naturally resolves to F, so even if the C7 is a bit of a leap from where you ‘should’ be in the progression, it leads you right back to the path you were originally on.

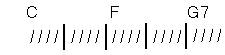

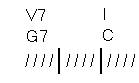

Original:

Substitution:

Now that we’ve covered the basics, I’ll go through fourteen different substitution ideas, and why each one works.

#1: Chord extensions . You can always add things to the core notes of a chord – playing C6 instead of C, or G9 instead of G7. Since all of the notes of the original chord are also in the substitution, they retain the original idea of the harmony. The one thing to pay attention to is the seventh note of the chord – if it’s a dominant chord to begin with (having a b7 note), you’ll want to keep a b7 tone in the substitution. If it’s a major chord to begin with, you’ll want to add a major (natural) seventh if you use one. Minor chords are the switch hitters – you can extend them either way… choose the one that places the seventh (7 or b7) in key.

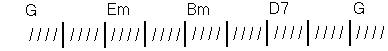

Original:

Substitution:

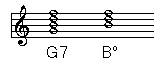

#2 – Chord simplifications . These are the opposite of extensions – you can use a diminished triad, like Bº (B-D-F) in place of a 7 th chord a major third lower – in this case, G7 (G-B-D-F). That works because the notes of the diminished triad are completely contained in the seventh chord:

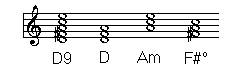

Other simplifications can snag just a portion of the original chord – if D9 (D-F#-A-C-E) is called for, a D triad works… as does Am or F#º. Each of those has three tones out of the original chord’s five:

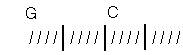

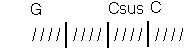

#3 – Chord suspensions . Suspended chords replace the third with a fourth, and that creates tension that wants to resolve – the fourth wants to move down a half step to the third. Use these for the first half of a chord – use Fsus-F-C or F-Csus-C in place of F-C.

Original:

Substitution:

#4 – Secondary Dominants . You can always use the dominant chord of your target for just part of the original chord’s duration. We did this with C7 and F just a little while ago, using a measure of each instead of playing two measures of F. This is called a secondary dominant, which I covered in an earlier article. Secondary dominants actually work for any chord in a progression, not just a dominant chord.

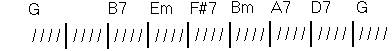

Original:

Substitution:

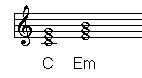

#5 – Relative majors and minors . If the original chord is minor, the major chord built on the third (C for an Am chord) will work as a chord substitution; if the original is major, the minor based on the sixth will work. In both cases, the substituted chord will have two of the original chord’s three tones:

#6 – Minor chords a third above a major . Like the relative minor (the sixth above a major), this chord will share two tones with the original:

#7 – Back and fourths (a term I invented to explain this one to students!) We’ve all seen how a blues progression moves I-IV-I before the V7-I cadence; you can use a chord of the same type, a fourth higher, for any chord – as long as you make a chord ‘sandwich’ (original-substitution-original). If the progression goes C-F-G7, you can play C-F-Bb-F-G7.

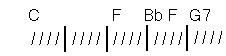

Original:

Substitution:

#8 – Diminished 7 th chords a third above a dominant chord . Since the simplification of a seventh chord into a diminished triad (substituting B-D-F for G-B-D-F) works, you can combine the simplification and extension to create a new substitution – using Bº7 (1-3-5-bb7, or B-D-F-Ab). The new chord will share three tones with the original.

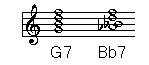

#9 – Dominant 7 th chords a minor third above a dominant chord . This one will share two tones – instead of G7 (G-B-D-F), you’d play Bb7 (Bb-D-F-Ab). You still have two tones in common. I’m showing this chord inverted, so you can more easily see how close they are:

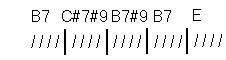

#10 – The tritone substitution . A tritone is three whole steps from the original chord. If the original is dominant – a 7 th , 9 th , 11 th , or 13 th chord – you can use any dominant chord that’s three whole steps up from the root of the original.

For example, if the original is G7 (G-B-D-F), a tritone up from G is C# – so you could use C#7, or the enharmonic Db7 instead (Db-F-Ab-C). This works for a couple of reasons… first, the new chord shares two tones with the old one; second (and really cool – one reason this substitution is used so often in jazz!), the new chord will almost always blend into the chords on either side by half steps.

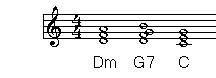

Let’s say the original change is Dm-G7-C. We plug in Db7 instead of G7… and now the roots move chromatically, D-Db-C. You’ve got one tone in Db that’s ‘connected’ to the chord on each side – F is in the Dm chord, and C is in the C chord – and even the Ab makes for chromatic steps A-Ab-G moving from the Dm chord to the C!

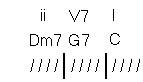

I’ll show the G7 and Db7 chords inverted, so you can more easily see the chromatic movement:

#11 – m7b5 chords a fifth above in place of a dominant chord . Instead of using G7 (G-B-D-F), you can use Dm7b5 (D-F-Ab-C). Again, you have two common tones from the original chord – the Dm7b5 is shown inverted to highlight the similarity:

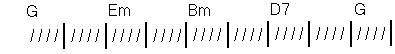

#12 – m7 ai fifth higher than a dominant (for part of a change) . This actually turns a V-I progression into ii-V-I, a very common jazz progression. Instead of using G7-C, you can use Dm7-G7-C.

Original:

Substitution:

#13 – Dominant alterations . These start getting tricky… when you have a dominant chord in the chart, you can place b5, #5, b9, or #9 in the chord. It’s best to establish the original chord first , then do your substitution. C7-F can become C7-C7b5-F, or C7-C7+-F, or C7-C7b9-F, etc. These work best when the dominant chord is going to resolve down a fifth. For more on altered chords, see my article “Altered States”.

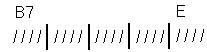

#14 – Stepping . Most chords can be ‘stepped into’ chromatically – you can substitute C-Ab7-G7 or A-F#7-G7 for a C-G7 change. You can actually over/under shoot your chord by quite a ways and still step into it, if you treat the change carefully… C-B7-Bb7-A7-Ab7-G7 can be made to work under the right circumstances.

Although stepping chromatically is the most common of this fairly rare type of substitution, it’s not the only choice – altered dominants work well when stepped into by whole steps, as in C-A7#9-G7#9-G7 for a C-G7 change. Unaltered dominants will even work when stepped into by minor thirds – you can use C-Bb7-G7 instead of C-G7.

You can even combine stepping with other substitutions – if you substitute an altered dominant, you can step into it by a whole step, like this:

Original:

Substitution:

Chord substitutions don’t come easily, and they don’t come naturally to most players. Don’t be afraid to experiment in your practice sessions – eventually you’ll be taking chords in unexpected directions, and resolving them to the original progression.

Salvador Mina

January 24th, 2016 @ 7:20 pm

Brilliant lesson! A very clear info for a beginner on jazz music chords as a rock guitarist.I’m no music reader,maybe you could include tabs on lessons.Thanks very much & more power!

bob

September 27th, 2015 @ 7:34 am

very helpful lesson just a beginner now I can sub chords just for the fingering ease ex C to Am

THANK YOU

Patrice Kodja

April 27th, 2015 @ 1:48 am

Thanks for this important chords dataware-house. Long ttime ago I was looking a complete chords substitution theory in other to analyze songs chord progression. Because as soon as one understand the how, he could transform it and a similar result interesting in listening and substitution gives that opportunuty. So once again thank you very much for sharing this mine of knowledge in that field. Regards

Tony

March 9th, 2015 @ 8:02 am

Cool man – a great (and well-explained and easily understood) article. I will begin practising these immediately (one at a time, of course!). It’s amazing how music theory can be simplified (with examples) so that the ordinary player (that’s me) can explore new musical avenues, without having to spend hours decoding!

Thanks again.

tom nelson

December 3rd, 2012 @ 5:49 am

I too have a bari uke. My 3 lower strings are tuned D, G, B. So I just play them as a guitar. I’ve lowered the high string to a hidg D, so my uke is tuned Open G. I has a low very mellow sound.

Good lesson

Thank you

Sal Pedi

May 25th, 2012 @ 11:14 am

chord subsitution is what I’m all about!… I play the baritone ukulele. I also have small fingers for an adult man, so I’m constantly looking for ways to “REACH” the chord which brings me to seeking out ‘SUBSTITUTE CHORDS” that sound sensational at the very least!.. its no small chore, believe me!…

I’ve been using “GUITAR CHORD BOOKS” to seek out these CHORD SUBSTITUES. You just might say that I’m a baritone uke player looking to sound like the great JOE PASS!.. I suspect that never gonna ever happen, but I do keep trying, regardless!…

What I’m also finding very irritating is that when I do find a song that I like, its usually the chords that are written that are not too good sounding for my ear!.. so, I don’t really know what gives with the way some of these songs are shown, cause, some songs sound just “Lousy”””…..

So, I continue my quest for “chord perfection” each day,seeking out these “subsitute chords” on the internet.. and, YES, I do agree that Dmi7b5 does sound great!…..

David Hodge

May 26th, 2012 @ 1:07 pm

Hi Sal

And thanks for writing. Using a baritone ukulele for jazz chords is inspired! Most jazz guitarists, when playing chords, often play chords that use four strings (or less) at a time, so your instrument of choice can certainly be helpful to you.

The biggest challenge, as I’m sure you’re aware, is that many times jazz players use the four “center” strings, if you will – that is, the A, D, G and B. Many times, too, they’ll play maybe the D, G and B strings together but use the low E string for a bass note. Or, likewise, they’ll use the three high strings (high E, B and G) for part of the chord while using the A or low E for a bass note.

A lot of times, your choices may not have to necessarily be a chord substitution, but rather a change of chord voicing, meaning that you’ve got the necessary note but you’re playing them in a different place on the neck. As you move up the neck of the baritone ukulele you should find yourself (even with small hands) able to make bigger stretches so you may be able to come up with different voicings of the same chord in a number of ways.

It’s also important to note that because you only have the four strings, and because they are tuned to specific intervals, some chords will need a different voicing simply to sound a bit more pleasant. Or interesting. Or ominous, depending on your arrangement.

Sounds like you’re enjoying your baritone ukulele a lot and I wish you much success in your ongoing search for more and more jazz chords – both in terms of chord substitutions and in different chord voicings.

Peace